Pages

56

104

But in the sense in which probabilities can be evaluated and made the subjects of mathematical calculation, a probability is a ratio of frequency in the long run of experience. This should never for one instant be lost sight of; and you should constantly ask yourself ‘Is there going to be any such experience in any way that can give the particular probability spoken of any real utility?’ The majority of treatises on probability tell us that if a man who never heard of the tides were to wander to some shore where the tides are very noticeable and were to notice that the tide rose in each one any number of successive half days, say N for N half days then the probability that it would rise on the next

57

106

half day would be (N+1)/(N+2). But what is the long run of experience that this represents? The tide it is said would be found to rise the next half day in N + I cases out of every N + 2 taken at random. But what are these N + 2 cases, I ask. They will say, I suppose, that they are the cases in which I observe a new phenomenon on N successive occasions. But it is impossible to suppose any solid statistics with such vague conditions. It all depends on what sort of facts one would call a new phenomenon. I go out with a friend for a walk in the country. We successively meet three acquaintances and my companion remarks that all three were baptists.

58

108

Has this any necessary bearing on what the communion of the next man we meet may be? Mind, I grant at once that some kind of argument might be founded upon it. But we are talking of arguments capable of being deduced mathematically; for the calculus of probabilities confines itself to mathematical reasoning. Two things are possible either that we meet successively four baptists or that we meet three baptists first and then a non-baptist. Now if these events are independent, which is the only case in which the calculus can be applied at all then representing by b the probability of a man met on that road being a baptist the probabilities of the two cases that are

59

110

now the only remaining possibilities were at the beginning of our walk b x b x b x (1-b) and b x b x b x b and now that there are no other possibilities the probability of the last man being a baptist is simply b4/b3 (1-b) + b4 = b/(1-b) + b = b That is, the probability is just what it was in the first place. If the events are not independent still the probability of the fourth man being a baptist must be greater the greater the antecedent probability of it. Yet the real argument that he will be a baptist has no force except from the fact that it is a strange thing to meet three baptists successively. But of course, to say that the events are independent, precisely amounts to saying that you cannot argue from one to another.

60

112

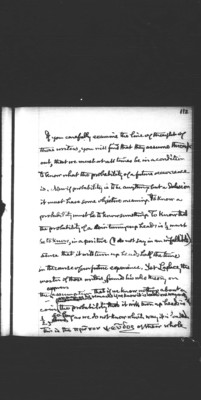

If you carefully examine the line of thought of these writers, you will find that they assume throughout, that we must at all times be in a condition to know what the probability of a future occurrence is. Now if probability is to be anything but a delusion it must have some objective meaning. To know a probability must be to know something. To know that the probability of a coin turning up heads is ½ must be to know, in a positive (I do not say in an infallible) sense that it will turn up heads half the time in the course of our future experience. Yet Laplace, the master of those writers, founds his whole theory on the express assumption that if we know nothing about a coin or even as he remarks if we know it is loaded one way or the other the probability that it will turn up heads is ½, so long as we do not know which way it is loaded. This is the πρῶτον ψεῦδος of their whole